Ventricular Assist Devices (VAD)

A ventricular assist device (VAD) is a mechanical pump that's used to support heart function and blood flow in people who have weakened hearts.

The device takes blood from a lower chamber of the heart and helps pump it to the body and vital organs, just as a healthy heart would. (For more information about how the heart pumps blood, see the Diseases and Conditions Index How the Heart Works article.)

A VAD may be used if one or both of the heart's lower chambers, the ventricles (VEN-trih-kuls), don't work properly.

Overview

You may benefit from a VAD if your ventricles don't work well due to heart disease. A VAD can help support your heart:

- During or after surgery, until your heart recovers.

- While you're waiting for a heart transplant.

- If you're not eligible for a heart transplant. (A VAD can be a long-term solution to help your heart work better.)

The basic parts of a VAD include: a small tube that carries blood out of your heart into a pump; another tube that carries blood from the pump to your blood vessels, which deliver the blood to your body; and a power source.

The power source is connected to a control unit that monitors the VAD's functions. The control unit gives warnings, or alarms, if the power is low or if it senses that the device isn't working right.

Some VADs pump blood like the heart does, with a pumping action. Other VADs keep up a continuous flow of blood. With a continuous flow VAD, you might not have a normal pulse that can be felt, but your body is getting the blood it needs.

Types of Ventricular Assist Devices

The two basic types of VADs are a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) and a right ventricular assist device (RVAD). If both types are used at the same time, they may be called a biventricular assist device (BIVAD). However, a BIVAD isn't a separate type of VAD.

The LVAD is the most common type of VAD. It helps the left ventricle pump blood to the aorta. The aorta is the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood from your heart to your body.

RVADs usually are used only for short-term support of the right ventricle after LVAD surgery or other heart surgery. An RVAD helps the right ventricle pump blood to the pulmonary (PULL-mun-ary) artery. This is the artery that carries blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen.

Both an LVAD and RVAD (sometimes called a BIVAD) are used if both ventricles don't work well enough to meet the needs of the body. Another treatment option for this condition is a total artificial heart.

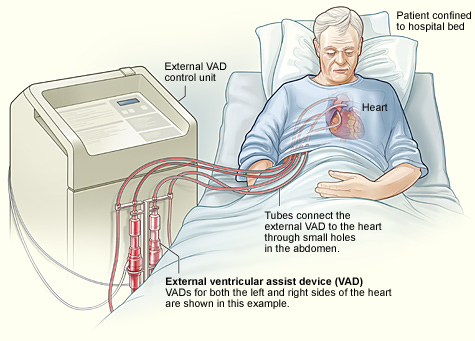

VADs have two basic designs. A transcutaneous (tranz-ku-TA-ne-us) VAD has its pump and power source located outside of the body. Tubes connect the pump to the heart through small holes in the abdomen. This type of VAD may be used for short-term support during or after surgery.

Transcutaneous Ventricular Assist Device

The image shows a transcutaneous BIVAD and how it's connected to the heart.

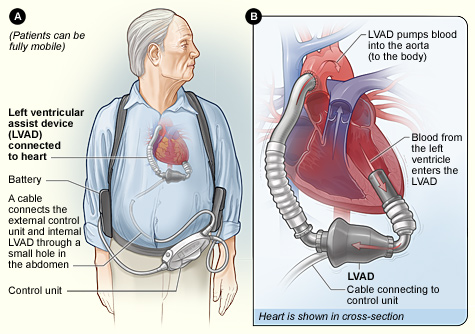

An implantable VAD has its pump located inside of the body and its power source located outside of the body. A cable connects the pump to the power source through a small hole in the abdomen.

Implantable VADs mainly are used when you're waiting for a heart transplant or as a long-term solution if you're not a transplant candidate.

Implantable Ventricular Assist Device

Figure A shows the location of the heart and the typical equipment needed for an implantable LVAD. Figure B shows how the LVAD is connected to the heart.

The design and type of VAD your doctor recommends will depend on your overall health, how long you're expected to need the device, and other factors.

Outlook

Until recently, VADs were too big to fit in many people's chests, especially women. Only people who had large chests could get one.

Now implantable VADs can fit in most adults and even some older children. Devices small enough for young children aren't yet available, but they're being developed.

Researchers have made advances in how well VADs work and how much they improve people's quality of life. In the past, VADs mostly were used for people who had end-stage heart failure. Now VADs also can help people who have earlier stages of heart failure.

Other Names for a Ventricular Assist Device

- Heart pump

- Left ventricular assist device, or LVAD

- Right ventricular assist device, or RVAD

Who Needs a Ventricular Assist Device?

You may benefit from a ventricular assist device (VAD) if your heart doesn't work well due to heart disease. Heart disease may prevent your heart from pumping enough blood to your body.

A VAD can help support your heart:

- During or after surgery, until your heart recovers.

- While you're waiting for a heart transplant.

- If you're not eligible for a heart transplant. (A VAD can be a long-term solution to help your heart work better.)

Short-Term Ventricular Assist Devices

A VAD can help support your heart for a short time while you're waiting for heart surgery. Your doctor may recommend a short-term VAD if you have a severe heart condition that can't be treated with medicine, such as heart failure, ventricular arrhythmia, or cardiogenic shock.

A VAD can support your heart and blood circulation for a short time before, during, and/or after surgery, until your heart recovers. A VAD also can help if you have heart failure and your doctors need more time to decide on a course of treatment.

Long-Term Ventricular Assist Devices

If you have heart failure and are waiting for a heart transplant, your doctor may recommend a VAD. If heart failure medicines aren't working, a VAD can keep you alive and improve your quality of life while you wait for a donor heart to become available.

If you're not eligible for a heart transplant, a VAD can be a very good long-term treatment solution. It can improve your quality of life and allow you to do many routine activities.

When Are Ventricular Assist Devices Not Recommended?

People who have certain serious health conditions, other than heart failure, that would limit their long-term survival usually aren't candidate for VADs. This includes people who have acute kidney failure, serious brain injuries, severe infections, and other life-threatening conditions.

What To Expect Before Ventricular Assist Device Surgery

Before you get a ventricular assist device (VAD), you'll spend some time in the hospital to prepare for the surgery. You might already be in the hospital getting treatment for heart failure.

During this time, you'll learn about the VAD and how to live with it. You and your caregivers will spend time with your surgeon, cardiologist (heart specialist), and nurses to make sure you have all the information you need about the VAD.

Before and/or after the surgery, you and your caregivers will learn:

- How the VAD works.

- Safety precautions.

- How to interpret and respond to alarms. (The device gives warnings, or alarms, if the power is low or if it senses that it isn't working right.)

- How to provide care in case of emergency, such as the loss of electrical power.

- How to wash and shower.

- How the VAD may affect travel.

You can ask to see what the device looks like and how it will be attached inside your body. You also may meet with someone who already has a VAD who can give you information. This person can answer questions about what it feels like to have a VAD implanted.

Your doctors will make sure that your body is strong enough for the surgery. If your doctors think your body is too weak, you may need to get extra nutrition through a feeding tube before surgery.

You also may have tests to make sure you're ready for surgery. These tests may include:

- Blood tests. Blood tests are used to check how well your liver and kidneys are working. Blood tests also are used to check the levels of blood cells and important chemicals in your blood.

- Chest x ray. This test is used to create pictures of the inside of your chest to help your doctor prepare for surgery.

- EKG (electrocardiogram). This test is used to check how well your heart is working before the VAD surgery.

- Echocardiography (echo). This test is used to create a detailed picture of your heart. Echo provides information about the size and shape of your heart and how well your heart's chambers and valves are working.

What To Expect During Ventricular Assist Device Surgery

Ventricular assist device (VAD) surgery usually takes between 4 and 6 hours. The process is similar to that of other types of open-heart surgery.

The team for VAD surgery includes:

- Surgeons who do the operation

- Surgical nurses who assist the surgeons

- Anesthesiologists who are in charge of the medicine that makes you sleep during surgery

- Perfusionists who are in charge of the heart-lung bypass machine that keeps blood flowing through your body while the VAD is put in your chest

Before the surgery, you're given medicine to make you sleep so you won't feel any pain. During the surgery, the anesthesiologist checks your heartbeat, blood pressure, oxygen levels, and breathing. A breathing tube is placed in your lungs through your throat. This tube is connected to a ventilator (a machine that helps you breathe).

A cut is made down the center of your chest. The chest bone is then cut and your ribcage is opened so that the surgeon can get to your heart.

Medicines typically are used to stop your heart during the surgery. This allows the surgeon to operate on your heart while it's not beating. A heart-lung bypass machine keeps oxygen-rich blood moving through your body during the surgery. (In some cases, LVAD surgeries have been done without using heart-lung bypass machines.)

For more information about heart-lung bypass machines, including an illustration, go to "What To Expect During Heart Surgery."

When the VAD is attached properly, the heart-lung machine is switched off and the VAD starts working. It supports blood circulation and takes over the pumping function of the heart.

What To Expect After Ventricular Assist Device Surgery

Recovery in the Hospital

Recovery time after ventricular assist device (VAD) surgery depends a lot on your condition before the surgery.

If you had severe heart disease for a while before getting the VAD, your body may be weak and your lungs may not work very well. Thus, you may still need a ventilator (a machine that helps you breathe) for several days after surgery. You also may need to continue getting nutrition through a feeding tube.

When you first wake up from VAD surgery, you'll be in the hospital's intensive care unit (ICU). You'll have an intravenous (IV) tube to give you fluid and nutrition. You'll also have a tube in your bladder to drain urine and tubes to drain blood and fluid from your chest and heart.

After a few days or more, depending on how quickly your body recovers, you'll move to a regular hospital room. Nurses who have experience with VADs will take care of you.

The nurses will help you get out of bed, sit, and walk around. As you get stronger, you'll be able to go to the bathroom and have a regular diet. The feeding and urine tubes will be removed. You'll also be able to take a shower. You'll learn how to care for your VAD while bathing.

In the hospital, nurses and physical therapists will help you gain your strength through a gradual increase in activity. You'll also learn how to care for your VAD at home.

Having family or friends visit you at the hospital can be very helpful. They can help you with various activities. They also can learn about caring for the VAD so they can help you when you go home.

Medicines

After VAD surgery, it's important to watch for signs of infection, especially around the area where the tubes or cable from the VAD exit the skin.

Signs of infection may include soreness over the VAD site, fluid draining from the site where the tubes or cable exit the skin, or fever. If you have these signs, tell your doctor right away.

You may get antibiotics before the surgery and for a few days after. This can lower the risk of infection. With most VADs, doctors also prescribe anticlotting medicines, such as warfarin (Coumadin®) and aspirin. These medicines help prevent blood clots from forming in your heart or the VAD.

When you have a device implanted in your body, the risk of blood clots increases. You'll likely need to take anticlotting medicines for as long as you have the VAD. You'll also have periodic blood tests to make sure the medicines are working properly.

Taking all of your medicines as prescribed is very important. Let your doctor know whether you have any side effects.

Going Home

After initial recovery from VAD surgery, you'll begin to get ready to go home. Your health care team will help prepare you for the transition. The team may include a heart surgeon, cardiologist (heart specialist), critical care nurse, physical therapist, dietitian, and social worker.

The team will help you practice living with the VAD at the hospital before you go home. They also will help you gradually adjust to living at home with the VAD. You'll leave the hospital and go home for a few hours and then come back. Next, you may go home for a whole day and come back to the hospital to sleep.

If these trips go well, your doctor may discharge you from the hospital. If you haven't recovered your strength enough, you may be sent to an intermediate care or rehabilitation facility for up to 2 weeks. This allows your medical team to make sure you're ready to go home.

Your medical team also will teach you what you need to know to live with a VAD. You may get some of this information even before your surgery. You'll learn how to care for the VAD, what to do in case the device gives a warning that it's not working right, and how to do normal daily activities like bathing.

For more information, see "What To Expect Before Ventricular Assist Device Surgery."

Activity Level

When you go home after VAD surgery, you'll likely be able to return to most of your normal daily activities. You may be able to return to work, engage in hobbies and sexual activity, and drive. Your medical team will advise you on the level of activity that's safe for you.

Travel

If you're waiting for a heart transplant, you need to be within 2 hours of the hospital in case a donor heart becomes available.

If you're not waiting for a transplant and want to travel, your medical team can advise you on any special arrangements you may need to make. People who have VADs can fly in airplanes and use all other forms of transportation.

Nutrition and Exercise

While you recover from VAD surgery, it's very important to get good nutrition. Talk to your medical team about following a proper eating plan for recovery.

Supervised exercise also is very important to give your body the strength it needs to recover. During the time when your heart wasn't working well (before surgery), the muscles in your body weakened. Building up the muscles again will allow you to do more activities and feel less tired.

Cardiac Rehab

Your health care team may recommend cardiac rehabilitation (rehab). This is a medically supervised program that helps improve the health and well-being of people who have heart problems.

Rehab programs include exercise training, education on heart healthy living, and counseling to reduce stress and help you return to a more active life.

Ongoing Care

You and your doctor will set a schedule for followup visits. This will help your doctor track how you're doing. The followup visits usually are the same whether you're waiting for a heart transplant or not.

After you leave the hospital, you'll likely be asked to visit an outpatient clinic weekly for the first month. After that, you may go every other week and then every other month for a certain time.

If you're on the waiting list for a heart transplant, you'll likely be in close contact with the transplant center. This is because most donor hearts must be transplanted within 4 hours after removal from the donor.

Some heart transplant centers give you a pager so the center can contact you at any time. You need to be prepared to arrive at the hospital within 2 hours of being notified about a donor heart.

Emotional Issues and Support

Getting a VAD may cause fear, anxiety, and stress. If you're waiting for a heart transplant, you may worry that the VAD won't keep you alive long enough to get a new heart. You may feel overwhelmed or depressed.

All of these feelings are normal for someone going through major heart surgery. It's important to talk about how you feel with your health care team. Talking to a professional counselor also can help. If you're feeling very depressed, your health care team or counselor may prescribe medicines to make you feel better.

Having family and friends around for support also can help relieve stress and anxiety. Let your loved ones know how you feel and what they can do to help you. They can play an important role in caring for you after you go home.

What Are the Risks of a Ventricular Assist Device?

Getting a ventricular assist device (VAD) involves some serious risks. These risks include blood clots, bleeding, infection, and device malfunctions. With left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), there's also the risk of right heart failure.

Thanks to newer VAD models, some of the most serious risks have decreased.

There's a small risk of dying during VAD surgery. There's also a small risk that your body may not respond well to the medicine used to make you sleep during the surgery. However, most patients survive and recover from VAD surgery.

Blood Clots

When your blood comes in contact with something that isn't a natural part of your body, such as a VAD, it tends to clot more than normal. Blood clots can disrupt blood flow and may block blood vessels leading to important organs in the body, such as the brain.

Blood clots can lead to serious complications (such as stroke) or even death. For this reason, you'll likely need to take medicines to prevent dangerous clotting (anticlotting medicines) for as long as you have a VAD.

Bleeding

The surgery to implant a VAD is complex, and bleeding may occur during and after surgery. Anticlotting medicines also raise the risk of bleeding.

Balancing the anticlotting medicines with the risk of bleeding can be hard. Make sure to take your medicines exactly as your doctor prescribes.

Infection

Implantable VADs attach a pump inside your body to a power source outside of your body. Transcutaneous VADs attach a pump outside of your body to your heart. For both types of VADs, the parts inside your body are attached to the parts outside of your body through a hole or holes in the skin.

Any time you have a hole in your skin, it increases the risk of bacteria getting in and causing an infection.

With permanent tubes connected to the outside through your skin, the risk of infection is serious. Your medical team will need to watch you very closely if you have any signs of infection, such as soreness over the site of the VAD, fluid drainage, or fever.

Device Malfunctions

VADs can malfunction (not work properly) in different ways. A VAD's:

- Pumping action may not be exactly right

- Power may fail

- Parts may stop working properly

With newer continuous flow VADs, the risk of malfunction may be decreased.

Right Heart Failure

Right heart failure means that the heart's right ventricle is too weak to pump enough blood to the lungs. This condition can happen as a result of getting an LVAD, which only supports the left ventricle.

The LVAD pumps a lot more blood than your weak left ventricle did. This puts more pressure on the right ventricle to pump the same amount of blood. The right ventricle may be too weak to match the pumping ability of the LVAD.

Thus, you may need extra support for your right ventricle. Usually, you only need this support until your right ventricle recovers or until you get a heart transplant (if you're a candidate).

Medicines may improve the function of the right side of your heart. However, sometimes a right ventricle assist device is needed for short-term support of the right ventricle.

Key Points

- A ventricular assist device (VAD) is a mechanical pump that's used to support heart function and blood flow in people who have weakened hearts. The device takes blood from a lower chamber of the heart and helps pump it to the body and vital organs, just as a healthy heart would.

- A VAD may be used if one or both of the heart's lower chambers, the ventricles, don't work properly.

- You may benefit from a VAD if your ventricles don't work well due to heart disease. A VAD can support your heart during or after surgery, while you're waiting for a heart transplant, or if you're not eligible for a heart transplant. (The device can be a long-term solution to help your heart work better.)

- The basic parts of a VAD include: a small tube that carries blood out of your heart into a pump; another tube that carries blood from the pump to your blood vessels, which deliver the blood to your body; and a power source.

- The two basic types of VADs are a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) and a right ventricular assist device (RVAD). If both types are used at the same time, they may be called a biventricular assist device (BIVAD). However, a BIVAD isn't a separate type of VAD. The LVAD is the most common type.

- Before you get a VAD, you'll spend some time in the hospital to prepare for surgery. During this time, you'll learn about the VAD and how to live with it. Your doctors will make sure that your body is strong enough for the surgery. You also may have tests to make sure you're ready for surgery.

- VAD surgery usually takes between 4 and 6 hours. The process is similar to that of other types of open-heart surgery. You'll be given medicine to temporarily put you to sleep during the surgery.

- Recovery time after VAD surgery depends a lot on your condition before the surgery. While you recover, it's very important to get good nutrition and ongoing care, follow your treatment plan, and begin walking as soon as possible.

- Getting a VAD involves some serious risks. These risks include blood clots, bleeding, infection, and device malfunctions. With LVADs, there's also a risk of right heart failure. Thanks to newer VAD models, some of the most serious risks have decreased.

- The risk of dying from VAD surgery is small. Most patients survive and recover.

- Researchers have made advances in how well VADs work and how much they improve people's quality of life.